The Cultural Leranings of Ivan Moudov

At the end of the 19th century, a long time before Sacha Baron Cohen came up with Borat (1), Bulgarian writer Aleko Konstantinov created the character of Bai Ganyo – a coarse, over-confident traveller from a backward Balkan country (Bulgaria) who finds himself in the middle of modern, civilised Europe. Konstantinov’s Bai Ganyo travels to Europe (1895) is a criticism of the mentality of the newly-born petit bourgeoisie in post-Ottoman Bulgaria and a record of the frightening difference between the modern world and a country that had just emerged from five centuries of feudal Ottoman rule in 1878.

Since the end of the 19th century, Bai Ganyo has been for Bulgarians a shameful reminder of the cultural gap between their country and Europe and a source of painful recognition of otherness. The character’s journeys are an example of a failed, impossible cultural exchange of the kind in which both parties remain unchanged by the interaction – Bai Ganyo’s faith in himself remains unshaken despite the superiority of “Europeans”, while his peculiar manners merit little more than polite interest on behalf of his civilised hosts. Although Konstantinov is unambiguously critical of his protagonist’s “backward” morals and makes him less and less agreeable as the story develops, it is difficult for readers to identify with either one side or the other.

Modern-day Borat is similar to 19th century Bai Ganyo, except his travels to the U.S. are on a grander, more global scale. The story is inevitably more complex and Borat is not merely an example of the clash of two worlds – one historically isolated, the other endlessly driven by the media – but is also a caricature of the foreigner, a kind of fake foreigner who is not recognised by either his own people or his hosts. His experiences are equally absurd and confusing to both his alleged compatriots and to the foreigners who are the object of his “learnings”. Both sides are forced to see themselves through each other’s clichés of the other.

Ivan Moudov constructs his role as a cultural traveller in the field of the visual arts much like a contemporary Aleko Konstantinov and with a sense of provocation similar to Borat’s. His own “learnings” are deliberately filled with misunderstandings and are often outright scandalous, questioning not only the mechanisms of the world’s visual arts scene but his own story and role as an artist.

Ivan Moudov’s gestures bewilder and confuse. The object of his critique is never clearly identifiable, and it is difficult to say whether he is taking sides with “the East” or “the West”, whether he is for or against the system or even what exactly the system is. Unlike the travels of Konstantinov’s character, Moudov’s cultural journeys threaten to shake not only the world of the viewer but also that of the artist himself and the objects of his interest as a cultural tourist.

In Moudov’s work no one is innocent – not his own people nor the foreigners, the artist, the public or the institutions.

In his performance Traffic Control (2001) he dressed up as a Bulgarian traffic policeman and stood on a busy crossroad in Graz, Austria, controlling the traffic until he was arrested by local police. New Hope (2006) is a trap lift in which the only moving part is the floor: when the “lift” moves upwards, it compresses the passengers against the ceiling in a manner known from the Star Wars series.

In The Wind of Change (2005) the artist installed surveillance cameras inside the exhibition space and powered them with a wind generator. The installation (monitors linked with the cameras) is only on when there is enough wind to produce power. Moudov’s questions to us are: Where is change taking us? Is change a one-way phenomenon? Can fortuity replace ideology? Does power change when it moves from one place to another and changes dress/uniform? What happens to our hopes when we move towards them?

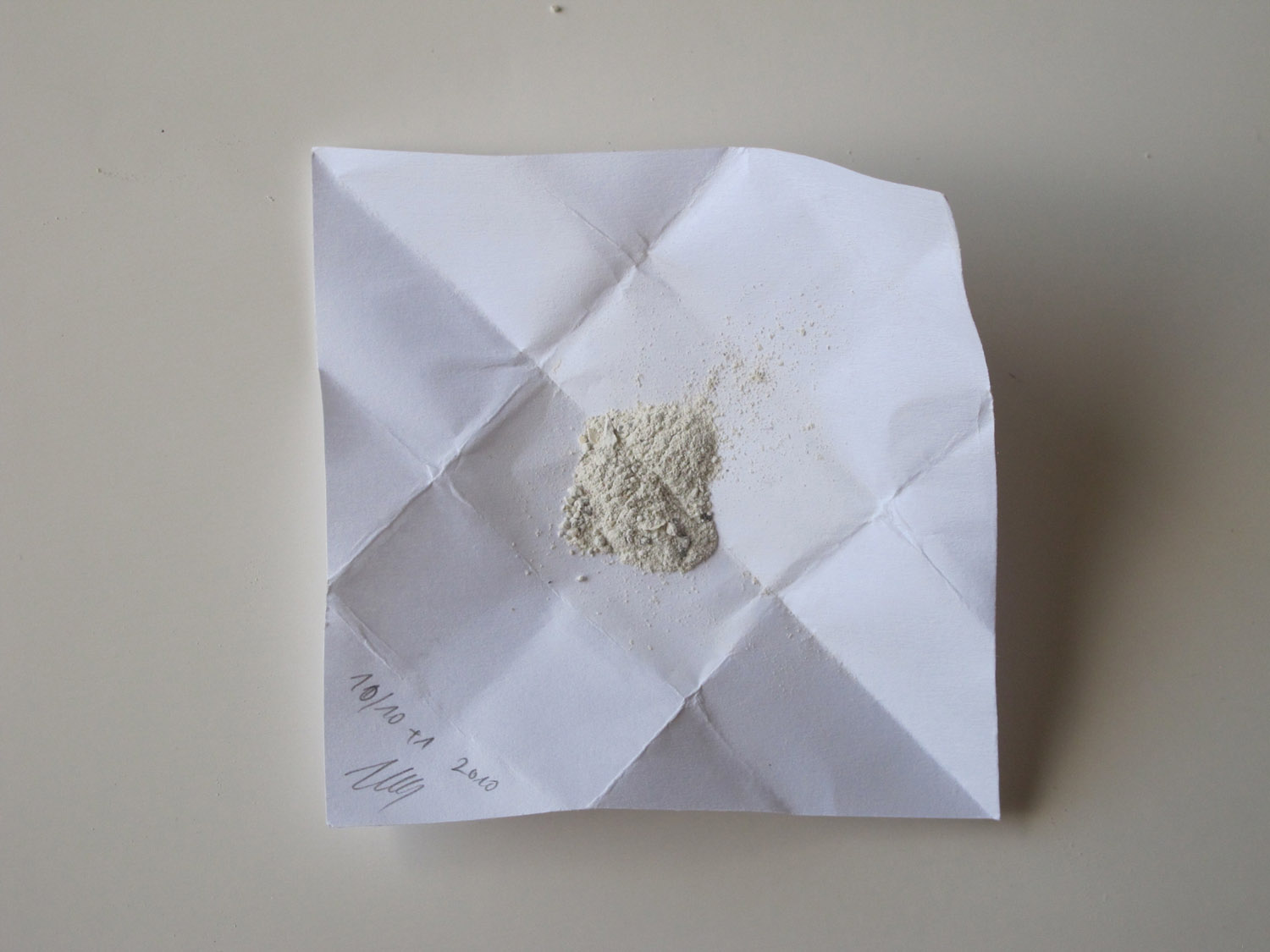

In 2002 Ivan Moudov began to compile his Fragments collection. The fragments are bits of works of art stolen by the artist, literally, from museums, galleries and art centres across Europe. Moudov laid out his collection—containing a vacuum cleaner mouthpiece from a work by Jeff Koons, a slide from a Douglas Gordon slide show, a fragment from Marcel Broodthaers’ eggshells and a nine of- diamonds playing card from a George Brecht installation – in an exact replica of Marcel Duchamp’s Boîte en valise. To date, there are four of these cases.

The role Moudov has chosen for himself in this work is one of an educated savage, a foreigner who is attracted by the world of Western high art but does not quite understand its principles and shows little respect for its institutions and the artworks themselves. Moudov’s Fragments echo the manner in which parts of the great European art collections were compiled at the dawn of museum history. In Fragments art history is reversed, and we witness a new expedition into “unknown” lands and a not-so-glorious attempt by the periphery to conquer the culture of the centre.

The art collector as a symbol of cultural centrality and public status is the object of similar “politically incorrect” analysis in The (African) Art Collector (1992-2000) by Nedko Solakov, who assembled some of the most valuable works from Western art museums and installed them in a straw hut. Both Moudov’s Fragments and Solakov’s Art Collector raise the question of the consequences of reversed roles: what happens when someone who was previously the object of collectors’ interest turns into a collector himself?

Moudov’s work, however, is not merely a museum mise-en-scene. To assemble it, the artist had to violate the integrity of other artworks and break the laws of several countries. He has thus pushed the collector idea and the museum concept to the point of absurdity. In his desire to become intimate with the artworks, to own and be able to display them in a new context (albeit not in their entirety), to offer them for re-appreciation, he has practically destroyed or at least damaged them.

His briefcase collection resembles a miniature curiosity cabinet. Unlike the objects in a curiosity cabinet, however, the artefacts in it have been taken exclusively from the works of established (institutionally legitimised) artists; their fragmentation brings the focus back on the variety of sources and materials from which they were initially made and seems to re-establish their original connection with the real world.

It is as if the museum nowadays is guilty by presumption and no mention of its name can pass without criticism of its autocratic role. Curiously, attempts to come up with an “alternative” to the museum have often had an “illegal” dimension. Duchamp’s Boîte en valise (1936-1941) is a case in point. During the German occupation of France, Duchamp travelled under a false identity as a cheese merchant and smuggled his miniature pieces to Marseille and from there on to New York. (2)

Moudov’s work, like Duchamp’s, is a commentary on the movement of artworks and their final destination as museum pieces.(3) But despite the fact that Moudov’s collection initially resembles Duchamp’s miniature museum, it actually turns the characteristics of Duchamp’s work upside down. The difference is not simply that Duchamp’s case contains miniature versions of his own works, while Moudov collects fragments from real works by other artists. Duchamp’s miniatures are (aura-stripping) reproductions of works which have little aura to start with (ready-mades). In his case they undergo yet another transformation resulting from their institutionalisation – they are re-contextualised in a museum environment. Moudov, on the other hand, is a passionate and unscrupulous art collector who does not even shun from destroying the works in order to fit them to the size of his briefcase. In this way, he paradoxically reinforces the authenticity of the works and turns them into a fetish. The fragment bears the aura of the whole and that of the artist who created it.

Since the introduction of the ready-made and the “dematerilisation” of art in the 60s and 70s, the value of an artwork has shifted from the work itself to the artist’s name and signature, which can sometimes be the only proof of a work’s authorship and authenticity. It is no coincidence that Ivan Moudov’s briefcases are accompanied by a description detailing the artist, the title of the work from which each fragment was taken and the museum where it is on display. The fragments – many taken from ready-mades – enhance the authenticity of the original “everyday objects”; they become objects touched by the hand of the artist. As with the trope of synecdoche, where a part of something stands for the whole, the meaningless, decontextualised fragments in Moudov’s work concentrate in themselves the value of the whole work. They can be related not only to the original work from which they were taken but also to the artist’s whole body of work and the reputation of the institution which owns and displays them.

Ivan Moudov’s portable museum is not an alternative to the art institution as the final destination of artworks. It is not meant to be and is incapable of existing outside the environment of the artworld – the only place where the fragments can re-acquire and enhance their original value. Outside and without the art system, the fragments are like the piece of broken guitar from the rock concert scene in Antonioni’s Blow Up, where once the concert is over and the discarded piece is found on the street, it is useless and undesirable.

In the end, both Moudov’s and Duchamp’s portable museums end up in the real museum. Just like Broodthaers’s studio, which the artist turned into a fictional Museum of Modern Art in 1968, was later reproduced (1975) as part of an exhibition in a real museum.

The critique of the museum is as old as the museum itself, dating from its birth in the 19th century, as early as the institutionalisation of the museum had begun. In the 60s and 70s of the 20th century such criticism is implicit in the works of many artists, some of whom founded their own “museums”. Ultimately, their criticism questioned the power of art institutions and the context in which artworks are presented and perceived. Significantly, Documenta 5 in Kassel in 1972 showcased “artist’s museums”. Marcel Broodthaers, Claes Oldenburg and Daniel Buren are but a few of the artists who have analysed various aspects of the museum as an institution. Broodthaers’s Museum of Contemporary Art, Eagle Department, to which Ivan Moudov often refers, raised questions of the place of the museum and the artist’s studio in the art world, of the principles of organisation of a collection, of the hierarchy of art collecting and art exhibiting, and of the ways in which artworks are valorised by art institutions. Ivan Moudov consciously grounds himself in this tradition.

At the same time, Moudov’s work on the role of the museum reflects a very different situation. Today’s artists do not see art institutions as embodiments of a status quo they are struggling against. The role of art institutions in determining the value, distribution and presentation of art is diminishing, while the importance of the market is growing. Modern museums are better adapting to the ideas introduced by artists in the 60s and 70s and often assume the function of studios as places of experimentation and chaos.

Moudov provides a counterbalance to the weakening role of the museum from a very local, Bulgarian perspective. As an artist from the periphery, where museum institutions have a different history from that in the West (e.g. Bulgaria has no museum of contemporary art), Moudov introduces a novel dimension to the global discourse on art institution – the lack of an art museum.

In 2005 the artist simulated the opening of a Museum of Contemporary Art in Sofia. Unlike Broodthaers (who opened his own Museum in his Brussel’s studio with a collection of wooden picture crates and post card reproductions of 19th c. French paintings), Moudov did not try to put together a collection or simulate an exhibition. In a way similar to Broodthaers, Moudov is interested in the symbolic value of the museum. His institutional analysis, however, focuses on the necessity for an inhabited (vs. a cold, neutral, uninhabited) space and on the relation of the museum to the city and the locality. He is interested in a type of communication which does not rely on “eternal” values but seeks to attract a wide and varied audience.

The opening of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Sofia (abbreviated in Bulgarian as MUSIZ) was publicised by a local art institution (the Institute of Contemporary Art) sending out a proper press release and putting up posters around Sofi a announcing the event (4). The choice of the recently renovated Podoueneh railway station as the place for the Museum was interesting and “legitimate” – a clever use of the world-wide trend to breathe new life into empty, disused spaces by inhabiting them with art. Rumours had gone around town that the station would soon be closing and discussions had already started as to what its best future use might be. During “the opening” the public filled up a waiting room that bore no trace of artistic intervention and was shocked to discover that it had to mix with people who were going about their business as usual, waiting for their trains. The public’s expectations were the most important component of the Museum’s fi rst exhibition. The event turned into an intriguing test of art processes in Bulgaria. Surprised by the absence of a real museum were not only the foreign ambassadors and cultural attachés (there to fulfil their duties) but also a number of key fi gures from the country’s art scene. Had they expected a museum of contemporary art to spring up overnight, out of the blue, with no public debate preceding its construction? Ivan Moudov’s MUSIZ quite likely set itself the ambition of provoking such a debate.

MUSIZ is only possible as a museum of appearance, not one of content, as a museum that exists through the image it projects via the media and not through the presentation of real art works. The railway station was a museum for one night only, an intention for a museum, a fi ctional institution for communicating with the world of art on an equal footing.

It is no coincidence that the museum has had a central role in Ivan Moudov’s “cultural learnings”. Walter Grasskamp sees the museum as “the first institution of globalisation” which in our day is already a “globalised institution” (5). Europe’s museum concept has been exported and functions throughout almost the entire world. In Grasskamp’s view, it is “the most successful European export in the context of cultural globalisation”(6). Ivan Moudov refers to this understanding when he says in an interview: “The MUSIZ project is specific to its locality but is connected to processes around the world. There is a new museum opening somewhere on the planet almost every month. In China only, there are plans to open 2000 museums in the next ten years” (7). If museums and museum collections support and legitimise the functioning of art from Europe to China, then it is no surprise that Moudov’s not-fully-civilised traveller seeks to legitimise himself by gaining access to the world’s art institutions and by creating institutions of his own.

As a contemporary Bulgarian artist, Ivan Moudov works mostly in the “Western” art tradition, although (as with many of his fellow Bulgarian artists) when he started his career his knowledge of his Western predecessors’ work was limited. In this respect, Fragments has the mission of filling the gaps, making up for a history that never was. In the artist’s own biography, Fragments are his way of catching up with the rest of the world. Moudov appropriates the Western tradition not only on an intellectual but also on a literal, physical level and produces forensic evidence for his development as an artist.

A closer look at the contents of Ivan Moudov’s briefcases reveals an interesting fact. Three of them contain fragments from artworks stolen from Western European art institutions, while, oddly, the fourth is designated for fragments from works by Central and Eastern European, Balkan or post-communist artists.

What is strange is that Moudov, who apparently works from a globalising, egalitarian impulse, should create such a division or reinforce an existing one. But the artist’s choice confirms a fact of life – the number of works by Central and Eastern European, Balkan or post-communist artists in the established art institutions in Western Europe is insignificant. Most of the fragments in the fourth briefcase have been taken from exhibitions dedicated exclusively to “other European”

artists. Equally intriguing is the fact that some of the fragments have found themselves in Moudov’s collection by offer from the authors of the works or with the silent consent of curators and directors of art institutions.

In Venice, the problems raised by Fragments will no doubt acquire new significance.

The Bulgarian pavilion at the Biennale, itself part of an exhibition based on national representations, is showcasing Moudov’s collection of cultural trophies – the artist’s pick from “the best” in the globalising art scene. His trophies link the national mini-museums in Venice together.

At the Biennale, Moudov’s collection will be shown for the first time in its entirety, and this will mark the official end to the artist’s collector and research activities. It is as if his very presence in Venice will divest him of his right to pretend to be a naïve foreigner, a mere observer of European art. By being shown in Venice, he will have gained the minimum requirements for the artist’s own history.

The end of Moudov’s fragments collecting, however, is not an end to his impulse to study the mechanisms and insignia of the globalised art world. In Venice the artist will be developing further his idea of integrating the separate territories of national pavilions by offering their curators the opportunity to open their exhibitions with Bulgarian red wine produced especially for the occasion.

Wine drinking is a friendlier ritual than looking at fragments broken off from famous аrtworks and has a far greater globalising potential. Quite likely, this idea is also rooted in Moudov’s thirst for commentary on the role of museums and art institutions. The wine offering can be interpreted as a symbolic sacrifice at the altar of the mystic role of museums (after Buren) (8), a role which no institutional metamorphosis from the last few decades has been able to take away.

(1) From the film, Borat: Cultural Learnings of America for Make Benefit Glorious Nation of Kazakhstan, 2006.

(2) Jean Clair. Marcel Duchamp, Catalogue Raisonné de l’oeuvre, 1977. Vol. VII, Paris.

(3) Benjamin Buchloch interprets the creation of Duchamp’s Boite en valise in the light of “the dialectic of institutionalisation and the transformation of the artistic practice into the object of the aesthetic cult on the one hand and the conditions of technical reproduction as he has introduced them into the high art discourse with the definition of his ready made on the other”, in A. A. Bronson and Peggy Gale, eds. Museums by Artists, (Toronto: Art Metropole, 1983), 45.

(4) MUSIZ of Ivan Moudov was realized in 2005 as a Resident Fellow’s project of the Visual Seminar, a long-term project of the Institute of Contemporary Art-Sofia and the Center for Advanced Study Sofia. Visual Seminar took place in the framework of relations, a project initiated by the Federal Cultural Foundation, Germany.

(5) “So the Baroque chamber of curiosities were early agents of globalization, as they brought objects from the entire known world to Europe, from which images of the world were formed there. The museum, in this early form, was therefore already an institution of globalization.” Walter Grasskamp. “The Museum and Other Success Stories in Cultural Globalisation.” CIMAM 2005 Annual Conference. Museums: Intersections in a Global Scene. http://forumpermanente.incubadora.fapesp.br/portal/events/meetings/reports/sessao2

(6) Ibid

(7) Interview to be published in: Gavin Morrison and Fraser Stables, eds. Lifting, (Edinburgh: Atopia Projects, 2007).

(8)Buren defines the museum as: “Privileged place with a triple role: Aesthetic, Economic, Mystical.” “The Museum (The Gallery) constitutes the mystical body of Art.” Daniel Buren. “Function of the Museum,” in A. A. Bronson and Peggy Gale, eds. Museums by Artists, (Toronto: Art Metropole, 1983), 57.

text

text