A trick in a trick in a trick in a...

Emanuele Guidi: Could you tell us how you learned the trick of breaking the coin with one hand? Is there any particular story behind it? What triggered your impulse to use it in your work?

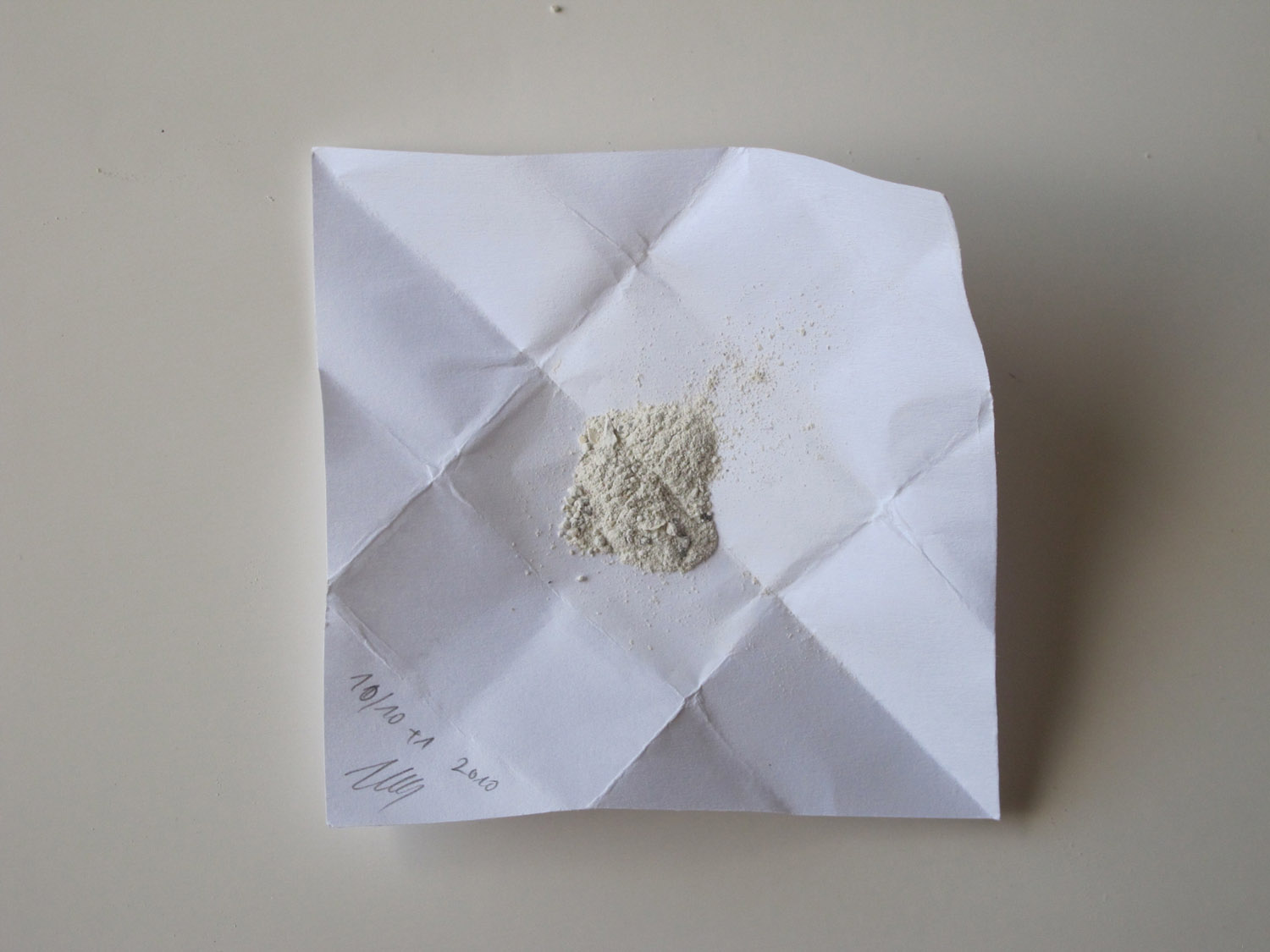

Ivan Moudov: I “bought” the trick a few years ago from a Romanian customs officer, on the border between Romania and Bulgaria. He asked me if I believed he could separate the ring from the inner part of a one euro coin with one hand. He did it and then asked me for five euro, because “Now you know the secret”. It was the quietest low-level corruption set-up I’d ever experienced. Then I started practicing the “magic trick”

and I called it the Romanian Trick. Last year I turned the trick into a performance and offered it to Moderna

Museet in Stockholm. The only difference was that I asked them for a lot more than five euro, promising them that I’d use the money to buy

a work from a Swedish artist. That’s how my own art collection was started.

EG: At the end of the day, the trick is quite simple. I mean, it doesn’t require a specific ability other than strength and patience, so anyone

who paid to learn it could feel a little tricked themselves. On the other hand, you create an extra value by destroying the ‘icon’ of economy itself.

And this is also a trick…

IM: It’s a trick in a trick in a trick. The first one is the trick I bought from the Romanian officer, the second one is that I’ve increased the value of

the original trick by turning it in to an artwork and the third is that at the end of it I have a collection. This last one is not really part of the work

but it’s there and it’s fair to mention it.

EG: Did the aesthetic of the trick affect the decision to use it? Looking at the videos, they remind me a lot of the studio performances of the

1970s. Also, the act of breaking the coin itself seems to give the coin (or what’s left of it) a sort of ‘sculptural’ connotation.

IM: Well, I am still very excited about what went on in the 60s and 70s and I find a lot of inspiration in that period. Although I finished my art

education after the political changes of 1989, our arts programme still had nothing about western art from the 60s and the 70s. My parents’

generation missed the 60s because of the communist regime. More or less, our generation caught up with that period in the 90s. That’s why

it’s not surprising that Romanian Trick, a work from 2008, is reminiscent of the 70s. And not just the 70s in the West. A lot of it is former Eastern

Bloc aesthetics from that decade. On the other hand, the work deals with contemporary problems like speculation in the art market,and

deconstructing/reconstructing art as a commodity. If by a 70s aesthetic you mean conceptual art, I have to say that I do not consider myself a

post or neoconceptual artist. At the same time, conceptual art is part of the heritage accumulated by contemporary art and it has a fair share in

my works too. So, yes, the aesthetics of the trick did provoke me. That’s for sure. About the sculptural aspects, the broken coins are just leftovers,

but I decided to use them in the documentation part of the work. Actually, you can wear them as rings, one euro for ladies and two euro for men

EG: What seems particularly relevant to me in your practice is your interest in the dynamics regulating the systems you intervene in. You

learn the rules of the game in order to push them to their limits. It happened in 14:13 Minutes Priority (2005) where you almost broke the

law, in Musiz (2005) where you staged a very effective marketing campaign and in a different way, it’s happening in Romanian Trick where you’ve

really rephrased the art market rules and so forth...

IM: When I initiate my performances and actions I don’t always have a clear idea of what is going to happen. 14:13 Minutes Priority, for example,

deals with the time. And so the duration of the performance became the title of the work. It was about how long I could survive in this specific

situation. I was bugging the system and it was possible because the system is not perfect. It’s about these 14 minutes of “freedom”.

For MUSIZ it was a bit different. I wanted to focus public attention on a certain problem – a missing museum. I wanted to start a public discussion.

I managed to do it quite easily -- all it took was one week of preparation.

I organised a fake opening of a new Museum for Contemporary Art (MUSIZ) in an old railway station in Sofia and invited more that 400 people to it. When the guests arrived, there was nothing there but other people waiting for their trains. Afterwards, there were a lot of organisations who announced they were going to work towards creating a museum, but it was just cheap PR. Nobody in Bulgaria wanted a museum. And that’s OK. It was shocking for me when I came to this conclusion but I’ve accepted it now. So with MUSIZ, I didn’t use the system. The system gave me a lesson and as an artist I am happy that my work is teaching me.

EG: I remember an email you wrote me in 2007 when Bulgaria became an EU member, saying that you were finally crossing the borders of several EU countries by car, free from any visa restrictions. That same year you presented Wine for Opening (2007) at the Venice Biennale in almost every pavillion as symbol of sociality and conviviality that allowed you, again, to go beyond the national structure of the exhibition…

IM: The Bulgarian participation in Venice was a real soap opera. It was our first and probably last national pavilion. I don’t want to go into details but suffice it to say that the pavilion was supported by a Belgian collector but not by the Bulgarian state. It was a big shame for Bulgarian institutions. The curator chose me because she new I could make some noise not only around myself but around the pavilion as well. Wine for Openings is not my favourite work, but in combination with Fragments was the best I could offer for the Biennial. The idea was for people to find out that this year there was a Bulgarian participation. At the same time, I wanted to play with the quasi Olympic status of national presentations. I find them quite annoying. The Venice Biennial is one of the most conservative anyway – it’s more like a carnival – so why not wine for free, Bulgarian hangover and divine intoxication. I delivered the wine personally to each pavilion. It took me almost a month. Actually, I was happy with the result.

EG: Probably Fragments (2002-2007) is your most well known work, also thanks to its quite provoking attitude. Beyond the pure act of ‘stealing’, what I find interesting is the act of ‘quoting’, the act of creating your narrative by processing others artists’work…

IM: The stealing is just one of the aspects in Fragments. I’m more interested in the business of collecting and the institutional troubles the work created. The stealing was just a tool. At the end of the project a lot of artists were asking me to exhibit them in the boxes. About the “quoting” and the creating of narratives by processing the work of others, I’m afraid that’s more curators’ practice. In Romanian Trick, I can say that I am curating my collections spatially, but the collection there is by-product, it’s not really part of the work. It’s more like a reward I’ve given to myself.

EG: It is true that in many cases that is more a curatorial attitude…I know they are quite different works but at least in Fragments (2002-2007) and Guide (2006) the process of your selection is not clear: is it the result of a focused desire or a premeditated plan or is it more the consequence of circumstances and instinct?

IM: Fragments was a very long project for my standards. I started it shortly after I graduated as an arts student. In the beginning, I was stealing everything I could possibly get my hands on. My collection looked more like a curiosity cabinet. Later, when I gained confidence, I started to have preferences, and in the end I became quite choosy – I was only stealing what I liked. With Guide there was no selection on my part. I recorded the audio guides from the museums. So it was the museums who made the initial selection. I made a big database of the audio guides and stored them in an audio guide device. There is a secondary selection which is up to the audience. You can use the database to curate your own shows.

text

text