Of Men and Things

For years now the work of Ivan Moudov has been dismantling the structure of the art institution as well as that of art as an institution. The particularity of his approach is that it comes from a perspective, which is simultaneously perfectly inscribed within the art world and deliberately outsider and amateurish. Moudov seems keen to play the well established art game and to conceive of his art as a form of institutional critique only to let it then fall into its own traps. Far from being simply a critique of the critique, his work turns upside down the very notion of critique and ends up subverting itself. One can say that the major quality of Moudov’s œuvre is that it never assumes to be cleverer than the rest of the world. On the contrary, it eagerly gets entangled into its own complicated plots and leaves no hope that art is some kind of a higher authority that can see and judge what the rest of us cannot.

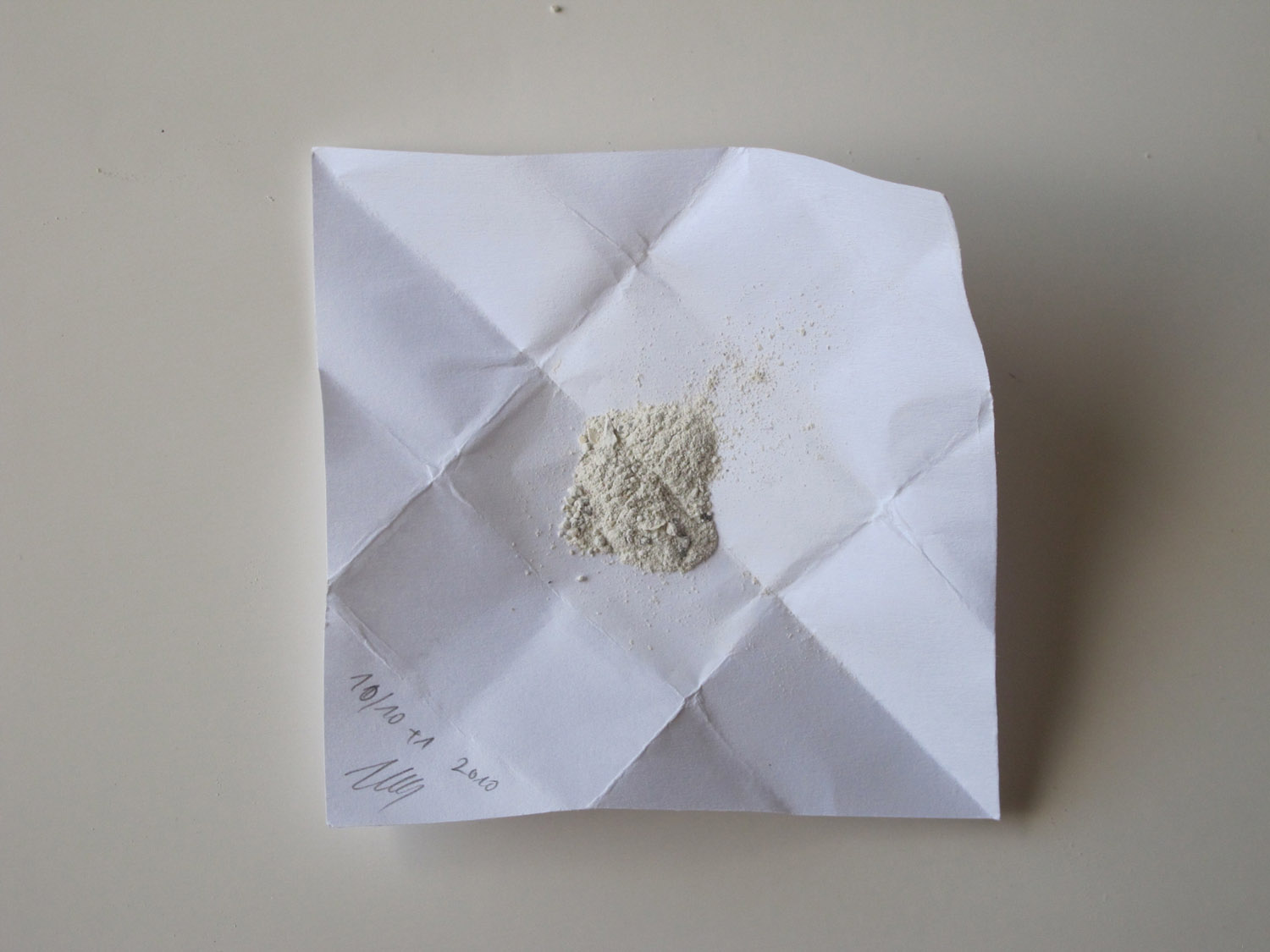

Rembember « The Romanian Trick », 2008- 2012? The work starts as an one Euro coin, gets split into two thanks to some street-smart trick, enters the art institution, transforms into a budget to buy a work by another artist and ends up as an expanding collection that is shown in the next institution interested in splitting coins in two. Got the trick ? Probably not, as there is no easy way to tell what exactly the artist is getting at. But if you don’t get completely lost on the way, you might eventually see how money turns into pure matter which transforms into museum sanctioned value, alternatively and endlessly materializing and dematerializing material, form, exchange. The story has no moral, it is just the possibilities life and art offer to create more art and chaos, ultimately a form of life.

Last year I went to see an exhibition of Ivan Moudov in Amsterdam. The unpretentious space of W139 gallery was empty, except for an A4 sheet of paper somewhere in the middle of a wall and a monitor, showing nothing but noise.

How was one to look at an exhibition that was seemingly insisting on nothingness at this day and time ? What more can we say about dematerialization and emptiness? Still there was nothing of the clean-cut cosmic void « dematerialized objects » of art often suppose. The void of Moudov’s exhibition was decidedly modest and very much of-this-world. There was the table for printed materials at the entrance, another table with all the drinks for the opening at the back of the space. The lack of art objects had not erased the rest of things out of the space. As I was hanging out in the semi-empty exhibition, thinking why Moudov has gone from an obsessive collecting of fetishes (as in « Fragments » (2002- 2007)) to a demonstrative refusal of objects, the exhibition literally started to unfold in front of my eyes.

There was the dripping ceiling, which didn’t seem so abnormal at first as the asphalt floor was creating a kind of an outdoor feel. Eventually, the drops got bigger and bigger and the puddle on the floor impossible to ignore. People had to move closer to each other and to the table with the drinks. There was too the sheet of paper, a work I actually knew about but experienced for the first time. The text on it stated simply that the door of the gallery cannot open from the inside and the visitors could leave the space only if there were new visitors coming in. As the night progressed I was able to leave the space few times, mostly thanks to people smoking outside, but I also had to ask random passers-by to open the door for me. In the image that appeared on the monitor for a split of a second I recognized another work I knew – « Wind of Change » (year), where a surveillance camera in the exhibition space is powered by a wind turbine on the rooftop, functioning only if there was enough wind. As more and more people filled in the space the drink table became the centre of the event. Although no one had approached me, I found out by other people that two men – Bulgarian immigrants in Amsterdam – offer the free coupons for the drinks that artists and staff sometimes get, for half the price. Later, as if to prove that life imitates art, a street band of Bulgarian folk musicians passed by accidentally and after a brief arrangement with the artist performed for the public of the exhibition.

Slowly people revealed themselves as the object of the show just as much as the asphalt floor, the wind, the invisible surveillance camera and wind turbine. Not so much in a participative manner but more together with things and undistinguishable from things that would enter into a relationship with one another as works of art put together in an exhibition space. This was neither a friendly, empowering relation between subjects, nor purely an objectifying move turning living people into instruments of the artist. While things were mostly absent, people were revealed as « comrades of things », to reverse Rodchenko famous phrase. People suffered physical limitations and discomfort, were subjected to surveillance but also to chance and the mercy of the elements (the wind, the water).

In Moudov’s exhibition people as things were neither diminished nor glorified. The demand for subjectivity was lifted like a burden - as things, humans did not have to engender and control the world anymore, be an ever active agent, performing a semblance of freedom. Instead their actions were limited to the range of the relationships between things. As Hito Steyerl remarked in an essay about things, the struggle of emancipation has always been the one of becoming a subject. Feminists wanted to abolish the objectification of woman for instance. But subjects are not as free as it seems. They are always already subjected. Moreover their subjectivity has today become a model for capitalism. Creativity, intellectual work, vitality and constant activity, interpersonal relationships and connections, these are all qualities that today bind people to service to the system instead of offering an escape and a possibility to develop one’s full potential freely. « The neoliberal subject, says D. Diederichsen, is exhausted by its double function as responsible agent and object of the action. » If an object was once the alienated and enslaving product of human labour, then in an immaterial economy based on knowledge objects become full of potential again, as they are least invested with the ideology of the new neo-liberal system.

Steyerl puts the question bluntly: « How about siding with the object for a change? Why not affirm it? Why not be a thing? An object without a subject? A thing among other things?” Or if we are to take Rodchenko’s appeal for elevating things to the status of comrades of humans, why not we humans be comrades of things instead? There is much we can learn from things, as things are not necessarily products or commodities – probably the only forms material things can take in capitalism. A thing might be an object, but not necessarily so. (the thing has emerged as something that is both more and less than an object. In W. J. T. Mitchell’s words:

“Things” are no longer passively waiting for a concept, theory, or sovereign subject to arrange them in ordered ranks of objecthood. “The Thing” rears its head—a rough beast or sci-fi monster, a repressed returnee, an obdurate materiality, a stumbling block, and an object lesson.5 ) An object freed of the commodity form is probably what a human freed of his subjective pressures could be – a sort of thing with limitless potentialities. A commodity is different from a thing because of its subject-like qualities. A commodity is a fetish, a thing endowed with a twisted soul, a thing that enters in relationships with other things in a very specific mode - exchange. A thing on the other hand, as Rodchenko suggested, could be a human counterpart. The new man of the avant-garde project could not be created without the surroundings of radically new things, humans and things had to educate and elevate each other. The avant-garde conception of things already implied equality and interchangeability – after all humans aspired to the machine, the machine was not simply a counterpart but a model for the new humanity.

A thing, like a work of Ivan Moudov, has no moral, it’s neither bad, nor good, it’s just part of life, or rather a particle of life. The relationship between things in « % » were complex, failure and chance were integral part of it – wind turbine and surveillance camera had to negotiate with the wind. Things also depended on people – the door had to be negotiated through people. The door depended on people just as people found themselves prisoners of the door.

It is easy to understand the appeal of the thing as something that can potentially bridge the subject-object divide. It is also easy to relate it to a certain materialist turn in contemporary art which developed as a reaction to the increasing dematerialization of labour and capital. We might be tempted to see things as pure matter in reaction to the forceful animation the knowledge economy imposes on everything. (Products on the market more and more have “souls” and tell stories, they often state: I am.. I was created…Please treat me in a certain way…) But Moudov’s exhibition did not reduce things to opposites of commodities. It pointed out something important – a thing is not reducible to its materiality, a thing could take many forms, a thing should not give up the terrain of the immaterial.

This point was all the more clear as it turned out that in the gallery space behind Moudov’s show was hidden another exhibition by a group of artists. Through a discreet door the visitor was entering a meandering dark corridor that lead in a wide open space. There the structure of the labyrinth was made completely visible - with its plywood and cardboard walls, props and cheap wooden frames. This construction which initial purpose was to create the illusion of the labyrinth corridor in the front space was taking a life of its own. The props were further reinforced by piles of wooden bars, the frames were reflected in inclined metal rectangles, the plywood backed by stacks of styrofoam. The dominant straight lines of the materials were pointing towards the sky with a clear constructivist aspiration. But the hope and elan of the constructivist diagonals were here deliberately lost in the chaos of the materials.

On one hand there was the invisible «thingification» of humans in Moudov's part of the show (or may be the «annimation» of human things, a leap from the objectivation of humans not into some higher subjectivity but into the seemingly innanimate life of «things»), on the other hand, in the second exhibition – there was the pure materiality of things, beyond any purpose or meaning – construction materials which instead of building things transform into an aestheticised pile of rubbish.

Rubbish here does not have a pejorative meaning. On the contrary, rubbish is often taken by artists as a kind of Bathaillian «base matter» of our contemporary world. Although today garbage is also a kind of commodity – it is subjected to recycling and constant re-injecting into the world of profitable things – it nevertheless carries the aura of the useless, of the excess that defies all efforts to be framed and rationalized. It is no coincidence that Ivan Moudov has also commented on garbage in his work. In his piece «Garbage»(2009), the artist again prefers to change the relationships between things rather than explore materials or objects in themselves. Similar to «the Romanian Trick», «Garbage» pushes a situation to its limits without an obvious end in mind. During a residency in Switzerland, the artist negotiated with neighbours to take their houshold trash. He then loaded the bags in his car and drove cross the border to Germany, where he disposed of the bags in bins along the road. In another version of this piece, he simply installed trash bins in Germany with a label stating that the garbage disposed there will be exported to Poland.

The «matter», the actual garbage here is not of primary interest for the artist. Instead, it is the strange circulation, one similar to but not defined by exchange or the free flow of goods and capital, that makes garbage in this case a «thing». It becomes a comrade in the mirror world of material things. As soon as it tries to behave like us humans, the ridiculousness but also the tight grip of the rules that define our lives appear. Geopolitical considerations of course do play a role in this re-distribution of waste. In our highly regulated and profit-oriented world, waste very much like people can be an unwanted, clandestine element of society. In this work again Moudov walks the subtle line that makes things and people exist on the border of the law. By simply challenging what appears common sense, the artist again creates situations on the verge of the law, revealing the all pervaisive web of limitations but also showing ways to act and exist differently.

text

text