Preface

Upon entering the Kunstverein, the viewer’s glance is directed from the grand foyer over to the garden room. At its center: a table covered with empty wine bottles and glasses from the opening ceremonies remains standing. Over 100 bottles of red wine were uncorked and proffered there, a Bulgarian Cabernet Sauvignon, a Wine for Openings with a special label for the Kunstverein.

There was also a similar “Special Edition” on the occasion of the 2007 Venice Biennale that Ivan Moudov personally brought to all the national pavilions where it was served at the respective opening parties. Whoever attended a Biennale preview knows what this means: staggering from one party to the next and sauntering about the Biennale grounds with an empty expression the next morning. Ivan Moudov simply makes art out of that which is really its core.

Also in the Kunstverein’s garden room: large aluminum letters gleam from high up on the wall with Moudov’s German cell phone number. Perhaps the buyer will later also receive the corresponding SIM card that documents all of the artist’s contacts during his stay in Germany. Doesn’t the artist encourage self-revelation? The work is not enough. Studio visits with special membership groups and sponsors, the looks behind the scenes; that is what’s so tempting. Ivan Moudov also questions the mechanisms of the art scene and his own identity as an artist through the provocations invoked in his interventions.

A banister guides the visitor on the ground floor past objects, videos, and documentaries that all deal with his long-term project, the (still) fictitious “Bulgarian Muse- um of Contemporary Art!” (abbreviated “MUSIZ“), the opening of which Moudov announced in 2005 by means of a PR campaign: Hundreds of journalists, diplomats, and art enthusiasts followed the invitation and came to the supposed opening at a train station in a suburb of Sofia where nothing happened. The famous Champagne house Pommery later filled champagne for Ivan Moudov: 150 bottles for the “grand opening of MUSIZ,” as the label indicates. Until the time is right, the champagne will remain stored in Pommery’s vaults.

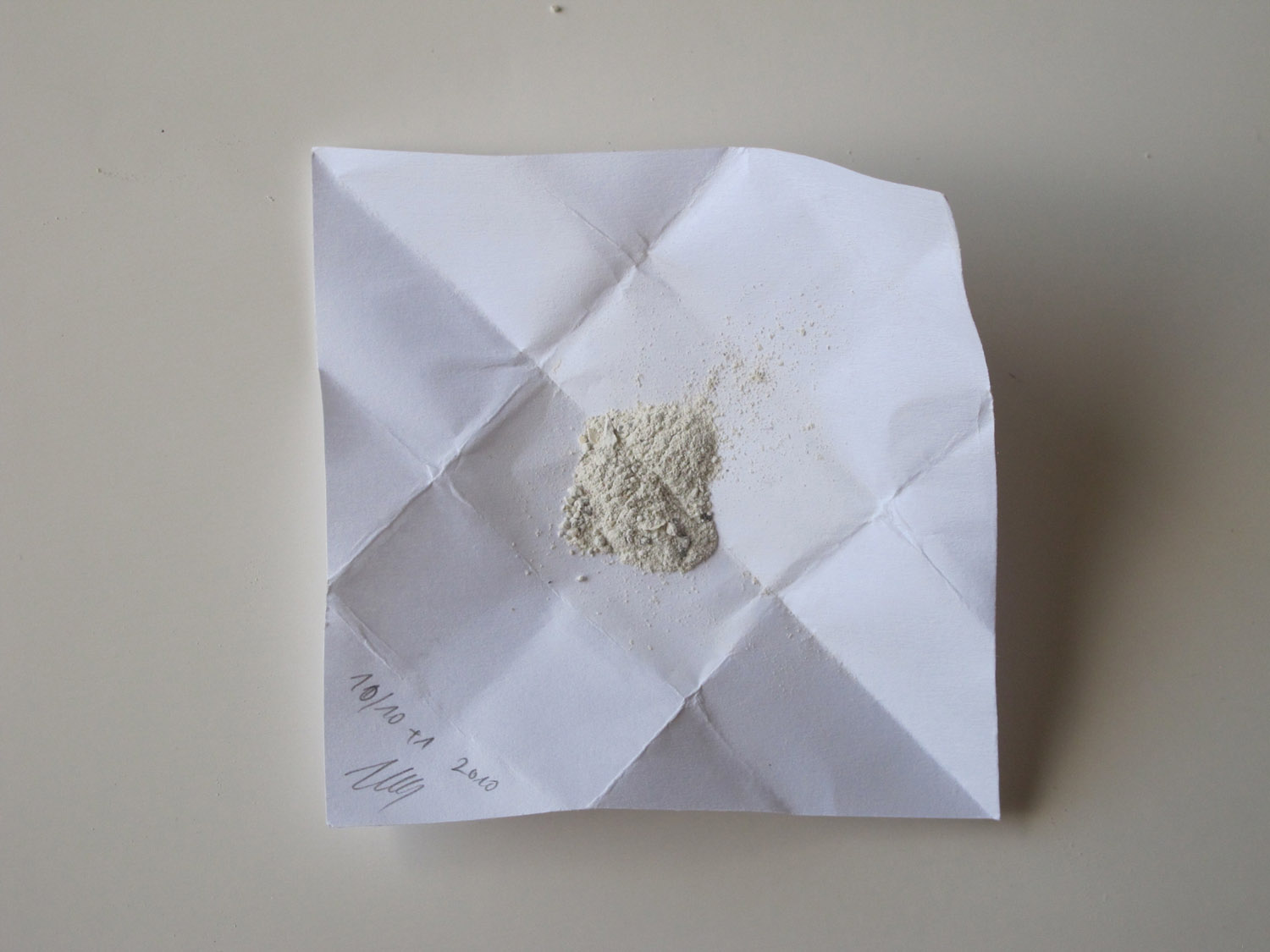

Moudov shows us how the collection of the not yet existing museum could look like one day with his art collection stowed away in suitcases: In his processual project Fragments (since 2002), he operates a form of contemporary archeology: he steals small especially targeted elements belonging to installations by famous colleagues like a slide by Douglas Gordon, a piece of fabric by Yinka Shonibare, or an eggshell by Marcel Broodthaers from museums around the world. The stolen goods are catal- oged and presented in a suitcase resembling Duchamp’s Boîte en valise. The space of

art becomes a crime scene and the stolen fragment is simultaneously a relic as well as a piece of evidence. A different type of appropriation, but alongside the attached criticism of institutions and representation these “stolen” artworks simultaneously reference Moudov’s role as an artist in a country the only one in the European Union that does not have a museum of contemporary art.

And Moudov continues to work on his collection of stolen art. Mysterious packages are piled up in front of the wall in the left wing of the ground floor: The sender gives them away: Ivan Moudov sent them to the respective exhibiting institution, the return addresses: art museums from all over the world. Do they contain further stolen art fragments? Who knows? Moudov provokes, amuses, and disappoints. The banister that seems to guide us through the exhibition ends in a cul-de-sac and whoever in the face of a promising view of the collection of suitcases in the radiant hall of mirrors overcomes the cordon, walks in front of a glass wall that forces one to turn back.

Ivan Moudov additionally works on his own factual collection which he making conscious use of Balkan clichés—finances by means of a sleight of hand (Romanian Trick) and presents in exhibitions on an equal footing alongside his own works. Moudov changes sides here from artist to collector and operates a power play. It is the buyers who determine the marketplace and increasingly also win influence over contemporary art, who steer it and are also in the position to also patronize young artists. This is a task that public institutions can hardly fulfill any longer due to the increasing pressure to raise visitor statistics and media reports. The sleight of hand to “core” 1 or 2 Euro coins with one hand were acquired by the respec- tive exhibition institution (for example the Moderna Museet in Stockholm, Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart or even the Kunstverein Braunschweig) who can reveal them to the exhibition visitor by means of video documentaries. In the case of Braunsch- weig, Moudov purchased from the money earned in this fashion what piece could be more suited Christoph Keller’s Visiting a Museum of Contemporary Art under Hypnosis. The video shows Keller describing the museum of his dreams while under hypnosis.

Moudov’s exhibition at the City Gallery in Sofia, which he realized together with Sibin Vassilev in 2006, consisted solely of the Guides that provide information about artworks which are not physically present. The texts were copied from the au- dio guides from various international museums. Moudov created an absurd image: visitors equipped with earphones with empty glances in front of empty walls. This naturally also concerns the fictitious museum that Moudov dreams of in Bulgaria, fitted with his favorites. But independent of this, Guides also deals with the con- temporary overabundance of information transmission that does not necessarily do much to sharpen our view.

Trusting one’s own view, one’s own perception, was also the concern of his early per- formances in which Moudov also directly integrated the viewer: In conjunction with his Traffic Control performance (since 2001), Moudov directs traffic in various Euro- pean cities dressed as a Bulgarian policeman and documents the diverse reactions of the motorists and authorities according to the respective cultural context in videos. Wildly gesticulating, but fitted with doubtful power by means of his uniform with the Cyrillic inscription “Policija,” Moudov undermines our trust in authority with

a twinkle in his eye. In 14:13 Minutes Priority he blocked roundabout traffic with a circulating motorcade until the performance was stopped by courageous motorists and the police. Moudov’s performances are ultimately aimed at tracing absurd situ- ations in our everyday environment and its organizational structure.

Moudov confronts the necessity of constant references or in the best case constant rediscoveries with another principle: The Already Made series shows things that already exist, but which are now filled with new contents, thus referencing a differ- ent type of thievery: the all-pervasive plagiarism, the theft of ideas. But factual theft has a tradition in art. Timm Ulrichs is the central model here, not only with his well-known Stolen Objects (1969–72). Ulrichs staged the actual theft of the work by an artist colleague and documented the four steps encompassed in this action by means of a series of photographs. The first shows Ulrichs measuring the painting to determine if it fits in his bag. Moudov now tautologically takes the first picture from Timm Ulrichs’s piece as the starting point of his own tetralogie. The first photograph depicts Moudov measuring Ulrichs’s picture and the second shows how Moudov in turn measures the photograph that was taken of his previous measuring action. The two subsequent photographs present the “Mise-en-Abyme Effect,” the picture in the picture in the picture, until Ulrichs’s original is no longer recognizable.

Moudov, who was trained as a painter, also undermines the classical subject of portraiture in a clever as well as humorous manner: Instead of inviting the sitter to a portrait session, he invites him to go out for coffee. But he has a fortuneteller analyze the photographed coffee grounds, presents them as an abstract as well as fictitious and intimate portrait in the manner of Kosuth’s concept art as a juxtaposition of photograph and text.

text

text