Romanian Trick

In many of his works, Ivan Moudov analyzes elements that shape the circulation and valorization of artworks in today’s world: the role of the art collection, the artist’s name, the institution museum and the ritual of exhibition openings.

In his Fragments series, he pilfered small parts of artworks from a number of established European museums and displayed them in briefcases — miniature museums of his own devising. The value of this work lies in the relationship between the stolen fragments and the “aura” of the original artworks as well as the “aura” of the artists who created them. In 2005, the artist simulated the opening of a Bulgarian Museum of Contemporary Art in the still-functioning Podouene Railway Station in Sofia, a project known as MUSIZ. Clever press releases, a new logo, posters, etc. publicly advertised and announced the fictitious museum and its opening. As part of his participation in the Venice Biennale in 2007, Moudov had his own wine produced. Branding it as Wine for Openings, he offered it to the curators of all national pavilions for their official openings.

In Romanian Trick all these strategies are developed further into a complex economy of their own. Romanian Trick constitutes a model of an all-encompassing artistic/economic practice with underlying mechanisms that appear almost as mystified and enigmatic as Marx’s theory of commodities and their value.

The story of this piece begins with a Romanian protagonist who sold the artist the “know-how” of how to break down 1 and 2 euro coins into their two metal components (the silvery inner cores and the outer brass rings for the 2 euro and vice versa for the 1 euro coins) for the price of 5 euros. The principle is that you pay five euros to learn the mysterious trick, but as a condition you must promise not to reveal the trick to anyone else without asking for the same price. The trick, as it turns out, is quite unspectacular, but you have the consolation of being able to recoup your losses by passing on “the secret of the trick” to others. The secret and the disappointment accompanying its disclosure are enough to make you feel as if you were a member of a secret society. It is this sense of mystique that sustains and furthers the enterprise.

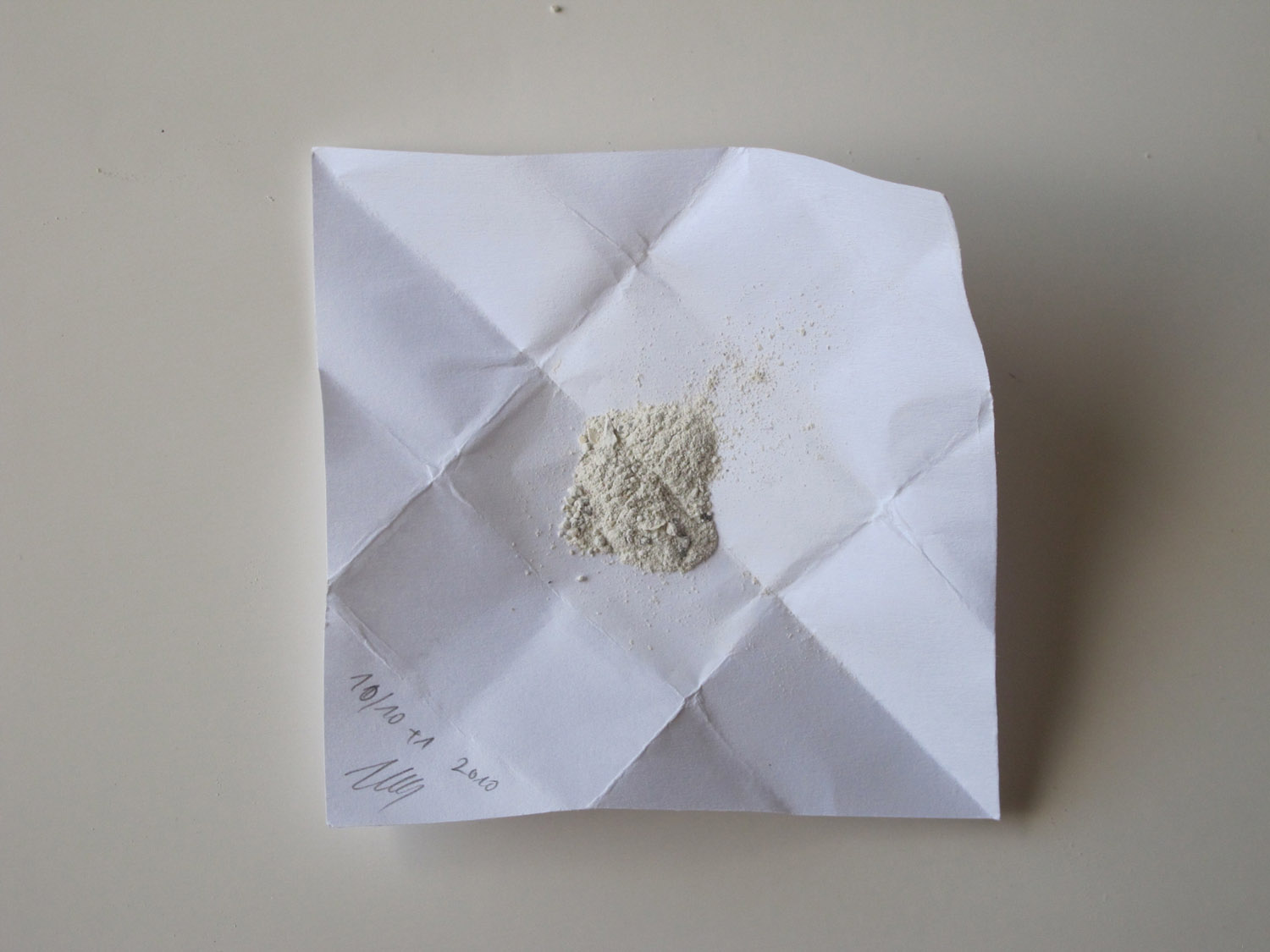

Moudov transfers the trick into the art world in different stages. The first one includes the exhibition of a performance, video documentation, a certificate and an object — a pile of separated coins. Revealing the secret to a large audience spoils the mystery and threatens the logic and continuation of the “Romanian Trick”. However, and this is Moudov’s own trick, the economic aspect (exchange-profit) of the enterprise is sustained and even improved. As the trick becomes an art piece its economic value is multiplied by hundreds.

At this next stage the trick is a paradigm for the creation of value in art. Its placement in the context of an exhibition implies a kind of swindle: you can buy the broken pieces of a 2 euro coin for 5 euros, or Moudov’s pile of broken 2 euro coins for the price of an artwork. In a world of dematerialized capital, the artist draws our attention to the material quality of money, to the form and function of an object of exchange, of a token. Moudov’s act of destroying money is ultimately an act of deconstructing the monetary value of the coins and by extension of the artwork. In Romanian Trick money is no longer a token of exchange but rather becomes a commodity itself.

As soon as the logic of the trick starts to seem obvious—the artist deconstruct- ing (and reconstructing) the value of art as a commodity—Ivan Moudov takes an unexpected turn that makes matters even more complex. Instead of just leaving Romanian Trick on the art market, he returns it to the level of exchange relationships by using it as a replacement for money in order to buy other artworks. This move involves (often publicly financed) art institutions and ultimately turns the artist into a collector and thus into the final consumer of an artwork. At this stage the Romanian Trick serves to finance the acquisition of another artist’s piece of work that is to become part of Ivan Moudov’s own collection. It might almost seem like a fair deal, but most of the institutions that take part in the project only have Romanian Trick at their disposal for the duration of a show. It is not the piece itself, but rather its exhibition that is exchanged. Moudov’s growing collection sub- sequently becomes part of the exhibition.

It is interesting to note that the artworks Moudov acquires also question the value of art or imply a certain sense of trickery. Olaf Nicolai’s Mirror—Cover (Vogue) for in- stance, puts any viewer on the cover of the millennium edition of Vogue magazine. Italo Zuffi, A Master’s Span (Ronni Horn Rebecca) fuses the names of two artists into one, thus inflating (or deflating) the fame of both. Maria Lindberg’s messy pile of 60 Meters of red thread on the floor leaves the audience with no other choice but to trust the artist’s claim and measurement. Christoph Keller’s video shows the artist Visiting a Museum of Contemporary Art Under Hypnosis.

Ivan Moudov’s aim is certainly not to unveil an underlying principle of the art economy or to offer a simple critique. He rather recreates his own model of existing relationships within this system in such an eccentric fashion that his critique—al- though somehow evident — purposely remains unclear and mixed with a confused business interest which seems to undermine the criticism.

The artist’s critique of the art world is pursued as an ongoing experiment where no aspect of the subject is left untouched. This is probably and paradoxically the only uncompromised way of critique for the artist today: One that does not fall back on any theoretical back-up or assume an outside position, but rather one that pushes and stretches the existing possibilities to their limits, until ruptures and breaches appear and hopefully persist.

text

text